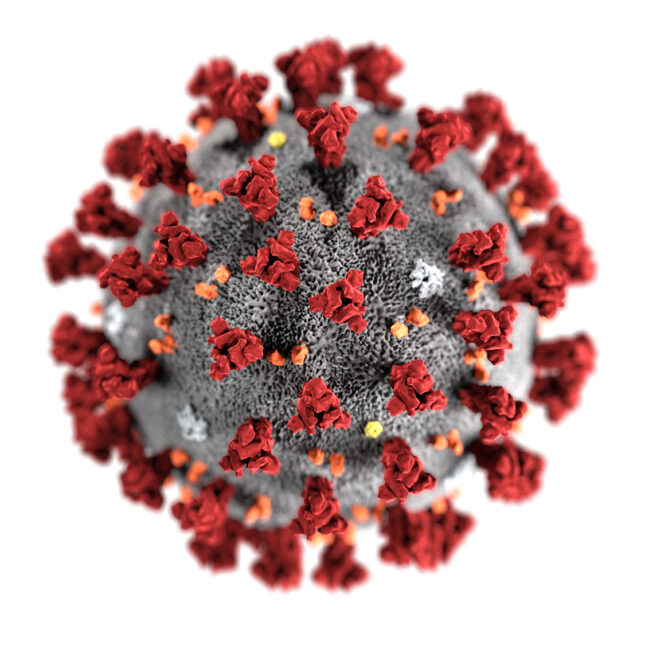

During this time—as our lives have been flipped upside down by an international pandemic and a national crisis—the relationship between non-human biology and mankind is at the forefront of everyone’s minds. Many people are living in fear. Some are in disbelief that our lives have been put on indefinite hold by a microscopic virus. And some still feel as though this has to have been expected, that this is Earth’s form of retaliating against all the damage humans have done to it. Even Kolbert addresses the damage an unknown and evolving pathogen can do to a species. She wasn’t referring to humans at the time, but to me it felt like a prophecy of COVID-19 as she says, “When an entirely new pathogen shows up, it’s like bringing a gun to a knife fight. Never having encountered the fungus (or virus or bacterium) before, the new host has no defenses against it” (204). She goes on to say that these interactions can be “spectacularly deadly.”

In The Sixth Extinction: An Unnatural History, Elizabeth Kolbert marries scientific evidence with personal anecdotes to create a compelling picture of man-made destruction all over the globe. Much of the book frames a bleak picture for the future, reminding readers that as biodiversity and ecosystems are destroyed, so will the Earth’s ability to sustain human life be destroyed. Kolbert exhibits the ways in which other species would be better off without the evolution and development of humans. However, her argument isn’t entirely dismal. While building the evidence of our threat to Earth and biodiversity worldwide in the first 12 chapters of the book, Kolbert argues in the last that not all is lost yet. Kolbert writes, “What matters is that people can change the world,” insinuating that it is what we do from this point forward that will alter the future of the planet (266).

I was particularly struck by Kolbert’s last couple of pages, when she reminds her readers that humans will not be the last ones standing, but how we treat the Earth will determine who is. While we have proved to be capable of altering nature and evolutionary pathways of other species, it’s critical to remember that how we change the globe now, in the midst of this Sixth Extinction, will leave its mark for millions of years, long after humans are gone. While it is our natural instinct to be most concerned with how climate change, loss of biodiversity, and other anthropogenic planetary changes will affect us as humans, it is crucial to recall that there is more to the planet that what we have brought to it. She ends the book by stating, “The Sixth Extinction will continue to determine the course of life long after everything people have written and painted and built has been ground into dust and giant rats have—or have not—inherited the Earth” (269).

Kolbert moves through the various causes and results of the previous five mass extinctions, which I was concerned she would use to draw the conclusion that because the Earth had survived five mass extinctions before, the anthropogenic destruction would ultimately be alright. I was relieved when she argued, in fact, the opposite: that an anthropogenically-caused mass extinction is “unnatural,” and therefore we should be intervening. I agree with Kolbert’s label for this sixth extinction, and I do not see this as contrary to Leopold’s stances on the relationship between humans and the environment. I think Leopold would agree with Kolbert’s assessment—that we need to establish sustainable ways to maintain the health of ecosystems and to protect biodiversity. And fast.

Leopold’s view considers mankind to be a part of the natural systems. While I think Kolbert may argue that the world was better off before man occupied it, I imagine she would also recognize that, at this point, humanity is irrevocably part of the system as a whole. Kolbert’s plan of action may be more drastic than one that Leopold would recommend, but I imagine she also desires a compromise that would allow humans and the earth to live in harmony. She wants the relationship between the two to be a mutually beneficial one, not a parasitic one.

As a future veterinarian—who recognizes the global interconnectedness of veterinary medicine with human and environmental health—I was particularly drawn to the passage about captive breeding the rhinos. I plan to specialize in zoological medicine, in hopes that I can aid in species’ conservation and public education on biodiversity. I also thoroughly enjoyed learning more about White Nose Syndrome and its devastating impact on bats. Finally, I think I was most surprised by the section on Neanderthals; I knew that many of us carry Neanderthal DNA but providing the story of our own evolution was a fascinating layer to add to the book.

The Sixth Extinction: An Unnatural History is an important book. I am already planning to lend this book over and over again, to recommend it to everyone I know. I believe Kolbert’s book could serve as a wake-up call to many—while she did not have to convince me about the disastrous impacts humans have had on the planet, the mingling of scientific and historical evidence with personal story may just convince those who need it.